Acute Myeloid Leukaemia (AML) is a rapidly progressive haematological malignancy that originates from the myeloid lineage of blood cells. It is a crucial diagnosis to be aware of when working in haematology or oncology, as early recognition and management significantly impact patient outcomes. This guide provides a structured overview of AML for junior doctors rotating through a haematology service.

Understanding AML

AML is characterised by clonal proliferation of immature myeloid blasts in the bone marrow, leading to bone marrow failure and subsequent cytopenias. The condition is highly heterogeneous, with multiple subtypes classified based on genetic and molecular features. It is most commonly seen in older adults but can also affect younger patients.

Clinical Presentation

Patients with AML often present with symptoms related to bone marrow failure, including:

- Anaemia – Fatigue, pallor, shortness of breath

- Neutropenia – Increased susceptibility to infections, fever

- Thrombocytopenia – Easy bruising, petechiae, mucosal bleeding

- Systemic Symptoms – Weight loss, night sweats, malaise

Some patients may present with complications such as leucostasis, which occurs due to a very high white cell count leading to symptoms of hyperviscosity, including headaches, confusion, and respiratory distress.

Investigations

A systematic approach is required when suspecting AML. Key investigations include:

- Full Blood Count (FBC) & Blood Film – Typically shows anaemia, thrombocytopenia, and circulating blasts.

- Bone Marrow Aspirate & Biopsy – Confirms the diagnosis with >20% blasts in the marrow.

- Immunophenotyping (Flow Cytometry) – Differentiates AML from other leukaemias.

- Cytogenetics & Molecular Studies – Essential for risk stratification and prognosis (e.g., FLT3, NPM1, CEBPA mutations).

- Coagulation Profile – Especially important if DIC is suspected.

- Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) & Uric Acid – Markers of high cell turnover.

Management

Management depends on the patient’s age, fitness, and genetic risk stratification.

Supportive Care

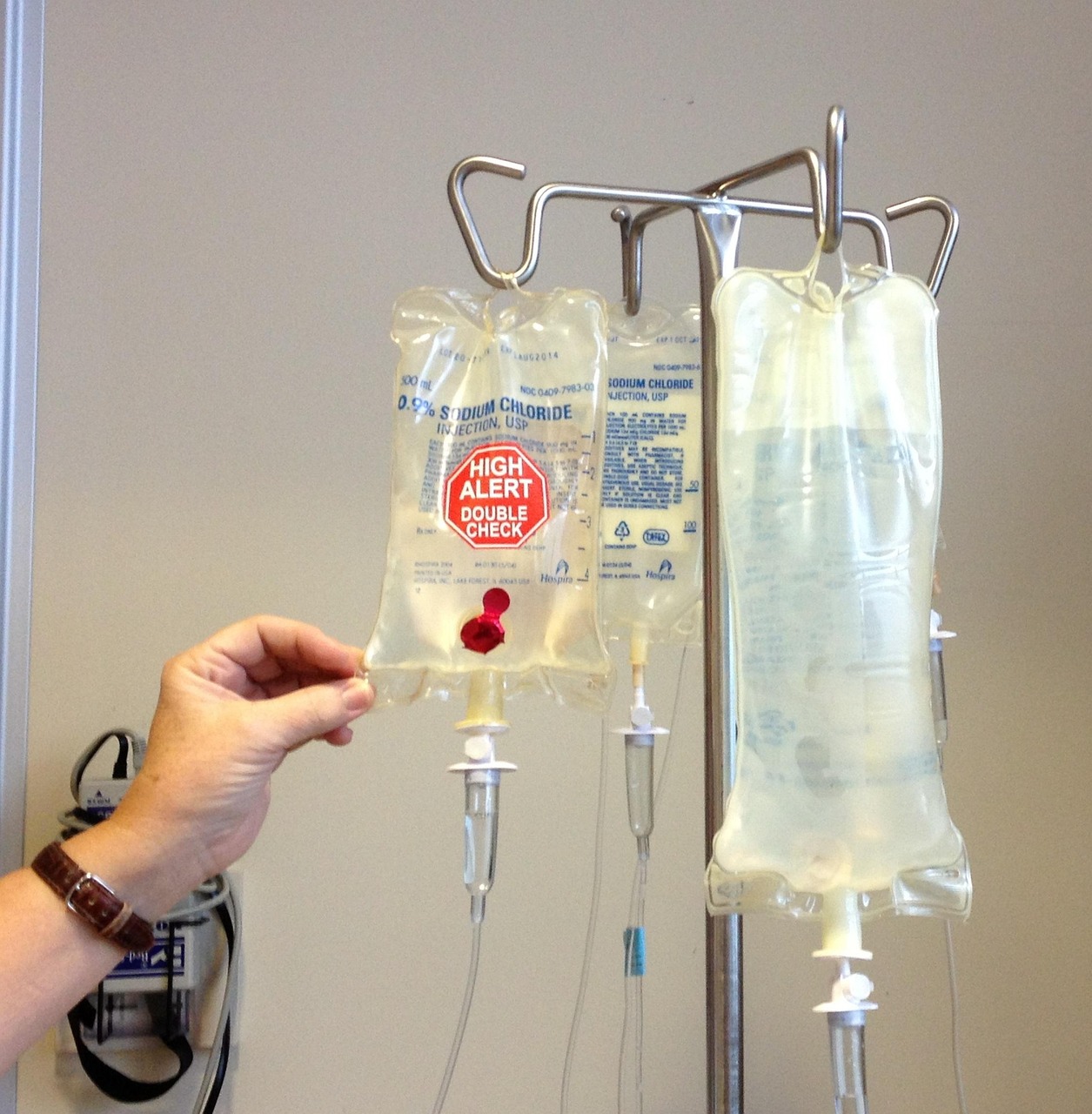

- Blood Product Support – Red cell transfusions for symptomatic anaemia, platelet transfusions to prevent bleeding.

- Infection Control – Empirical antibiotics for febrile neutropenia, prophylactic antifungals and antivirals in high-risk patients.

- Tumour Lysis Syndrome (TLS) Prophylaxis – Hydration, allopurinol, or rasburicase to prevent TLS.

Definitive Treatment

- Intensive Chemotherapy

- Induction Therapy – Standard 7+3 regimen (7 days of cytarabine + 3 days of an anthracycline such as daunorubicin)

- Consolidation Therapy – High-dose cytarabine or allogeneic stem cell transplant in high-risk patients

- Low-Intensity Therapy

- Hypomethylating agents (e.g., azacitidine, decitabine) for frail or elderly patients

- Venetoclax-based regimens for patients who are unsuitable for intensive chemotherapy

- Targeted Therapy (based on molecular mutations)

- FLT3 inhibitors (midostaurin, gilteritinib)

- IDH1/IDH2 inhibitors (ivosidenib, enasidenib)

- Palliative Care

- In patients who are unfit for treatment due to age, frailty, or comorbidities, the focus may shift to symptom management and quality of life.

- Supportive measures include blood transfusions, pain management, and symptom control.

- Discussions around goals of care and advanced care planning are essential in these cases.

Complications to Watch For

- Febrile Neutropenia – A medical emergency requiring broad-spectrum antibiotics.

- Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (DIC) – Seen in acute promyelocytic leukaemia (APL), requiring urgent all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA).

- Leucostasis – High WBC counts causing microvascular obstruction, often requiring leukapheresis or hydroxyurea.

- Relapsed/Refractory Disease – May require salvage chemotherapy or experimental therapies.

Prognosis and Follow-Up

AML prognosis depends on cytogenetic and molecular risk factors, patient age, and treatment response. Younger patients with favourable-risk AML can achieve long-term remission with intensive chemotherapy and stem cell transplantation. However, older patients or those with high-risk mutations often have poorer outcomes.

After treatment, patients require regular follow-up with:

- FBC monitoring for relapse detection

- Bone marrow biopsies post-treatment

- Long-term surveillance for complications such as secondary malignancies and graft-versus-host disease in transplant recipients

Key Takeaways for Junior Doctors

- Always suspect AML in a patient with pancytopenia and circulating blasts.

- Early bone marrow biopsy and cytogenetic testing are crucial for diagnosis and treatment planning.

- Supportive care, including infection control and transfusions, is vital in management.

- Recognising complications such as febrile neutropenia and DIC can be life-saving.

- AML treatment is increasingly personalised, with targeted therapies improving outcomes.

- Palliation is an important option for patients who are unfit for treatment, with a focus on quality of life.

AML is a challenging but fascinating disease that junior doctors will frequently encounter in haematology. Understanding its presentation, workup, and management will enable you to provide better care for your patients and work effectively within the haematology team.

Want to learn more? Our comprehensive haematology course provides in-depth case-based learning, practical management tips, and exam-focused content to help you excel during your haematology rotation. Sign up now at HaematologyForDoctors.com!

Leave a Reply