Have you ever wondered why we give patients with FLT3 mutated AML midostaurin during their induction and consolidation chemotherapy? Today we will be talking about the RATIFY trial to find out.

The RATIFY trial (CALGB 10603) was a pivotal phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study that evaluated the efficacy of adding midostaurin, a multikinase FLT3 inhibitor, to standard chemotherapy in adults aged 18–59 with newly diagnosed FLT3-mutated acute myeloid leukemia (AML). The trial enrolled 717 patients across 225 sites in 17 countries.

Study Design

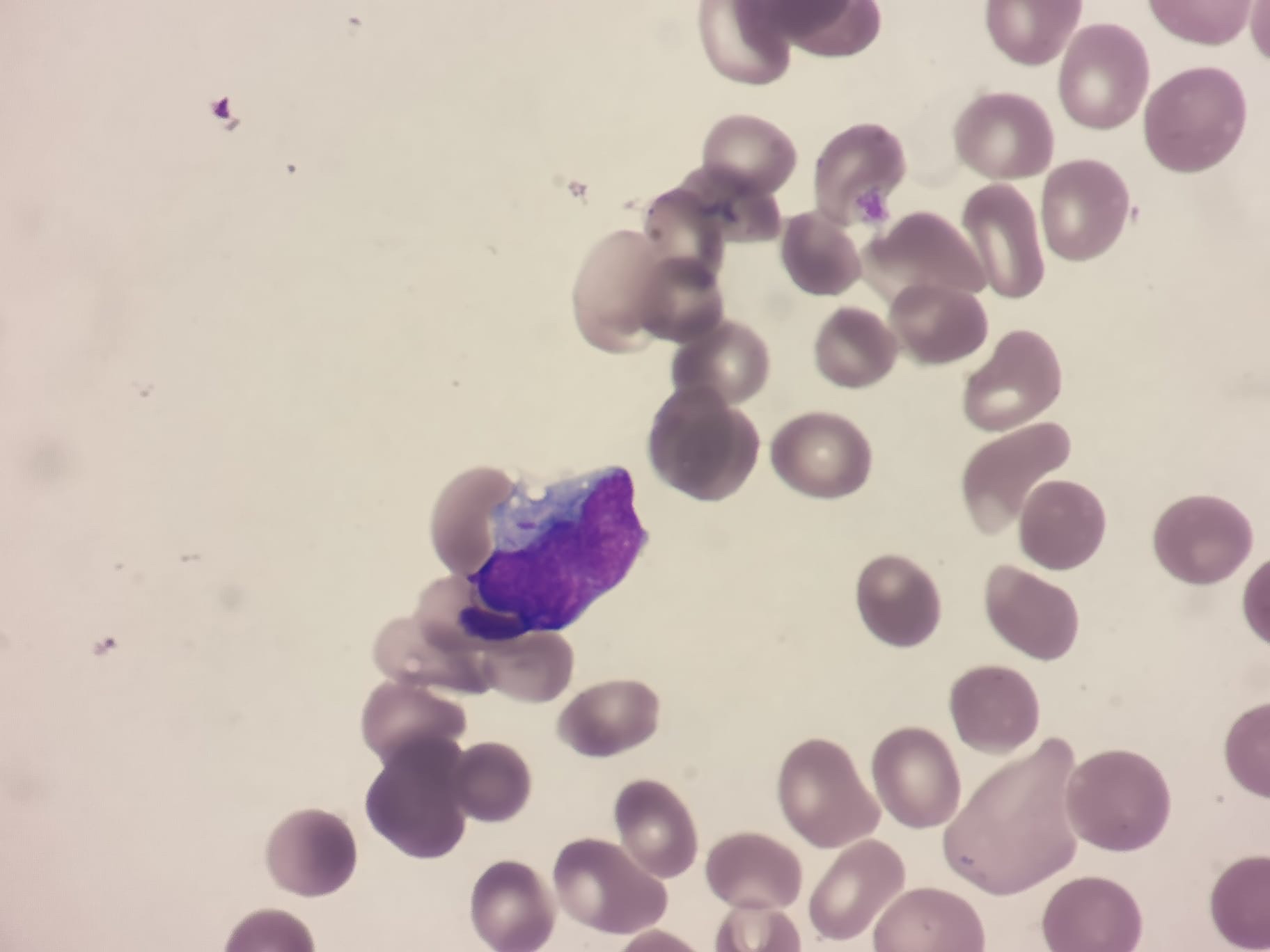

- Population: Patients aged 18–59 with newly diagnosed AML harboring FLT3 mutations (including both internal tandem duplication [ITD] and tyrosine kinase domain [TKD] mutations).

- Intervention: All patients received standard induction chemotherapy (daunorubicin and cytarabine). Those achieving remission proceeded to consolidation therapy. Patients were randomized to receive either midostaurin (50 mg twice daily) or placebo, administered during induction, consolidation, and as maintenance therapy for up to 12 months.

Key Outcomes

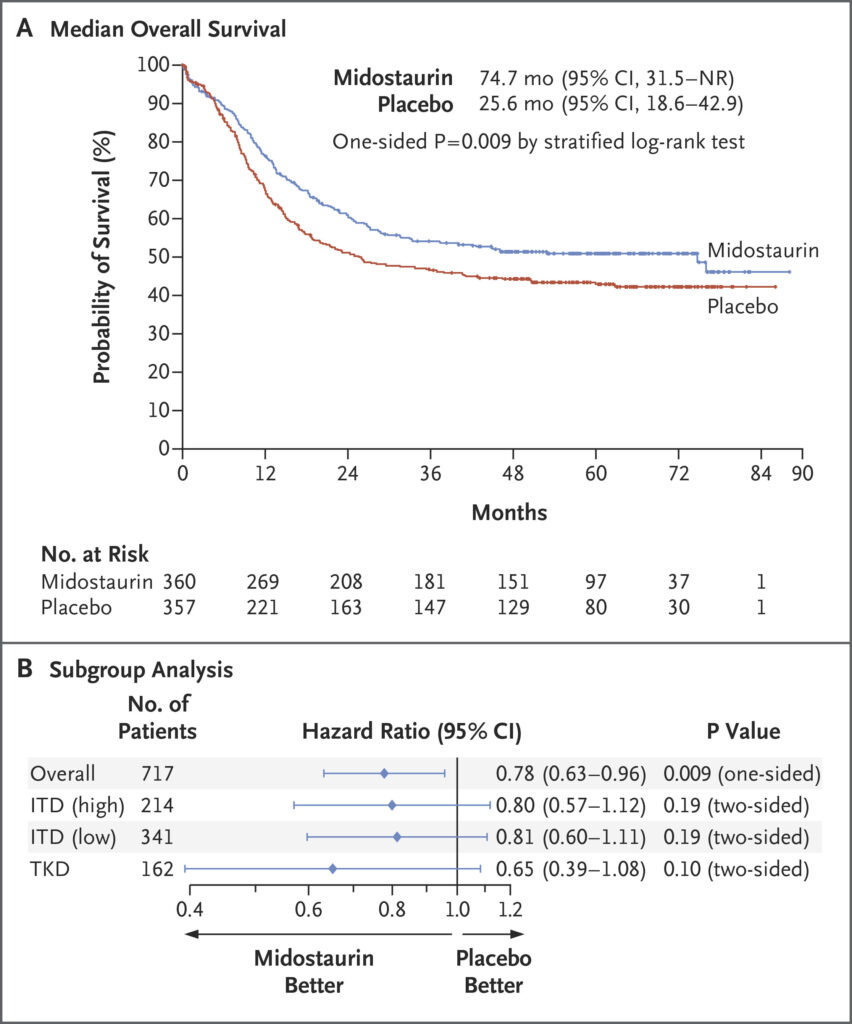

- Overall Survival (OS): The addition of midostaurin significantly improved OS. The median OS was 74.7 monthsin the midostaurin group compared to 25.6 months in the placebo group. The hazard ratio (HR) for death was 0.78(one-sided p = 0.009), indicating a 22% reduction in the risk of death.

- Event-Free Survival (EFS): Midostaurin also improved EFS, with a median of 8.2 months versus 3.0 months in the placebo group (HR = 0.79; p = 0.0067).

https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1614359

Long-Term Follow-Up

A 10-year follow-up analysis confirmed the durability of midostaurin’s benefit:

- OS Benefit: The survival advantage persisted over a decade, with a sustained improvement in OS for patients receiving midostaurin.

- EFS Benefit: The improvement in EFS was maintained, reinforcing the long-term efficacy of midostaurin in combination with chemotherapy.

Subgroup Analyses

Midostaurin’s benefit was observed across various FLT3 mutation subtypes:

- FLT3-ITD: Patients with both high and low allelic ratios of FLT3-ITD mutations experienced improved outcomes.

- FLT3-TKD: Patients with TKD mutations also benefited from midostaurin addition.

Limitations

- Age Restriction: The trial included only patients aged 18–59, limiting the generalizability of results to older populations.

- Maintenance Therapy: The study included a maintenance phase with midostaurin, but the specific contribution of maintenance therapy to overall outcomes remains unclear.

- Toxicity: While midostaurin was generally well-tolerated, grade 3 infections occurred in 52% of patients in the midostaurin group, comparable to the placebo group.

In summary, the RATIFY trial established the addition of midostaurin to standard chemotherapy as a new standard of care for younger adults with FLT3-mutated AML, demonstrating significant improvements in survival outcomes. However, considerations regarding its applicability to older patients and the role of maintenance therapy warrant further investigation.