Leukaemia is a group of malignancies affecting the bone marrow and blood, characterised by the uncontrolled proliferation of abnormal white blood cells. It is broadly classified into acute and chronic types, which differ significantly in presentation, pathophysiology, and management. This guide provides a structured overview to help junior doctors navigate the diagnosis and treatment of leukaemia.

Classification of Leukaemia

Leukaemias are divided based on cell lineage (myeloid vs lymphoid) and disease course (acute vs chronic):

- Acute Myeloid Leukaemia (AML): Rapidly progressive cancer of myeloid progenitor cells.

- Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia (ALL): Rapidly progressive cancer of lymphoid progenitor cells.

- Chronic Myeloid Leukaemia (CML): Slow-growing cancer of myeloid cells.

- Chronic Lymphocytic Leukaemia (CLL): Slow-growing cancer of lymphoid cells.

Pathophysiology

- Acute leukaemias arise from immature precursor cells (blasts), leading to uncontrolled proliferation and bone marrow failure.

- Chronic leukaemias involve the accumulation of more mature but dysfunctional cells, leading to a slower disease progression.

Clinical Presentation

Acute Leukaemias (AML & ALL)

- Rapid onset over weeks to months.

- Symptoms of bone marrow failure, including anaemia (fatigue, pallor), neutropenia (infections), and thrombocytopenia (bleeding, bruising).

- Systemic symptoms such as fever, weight loss, and night sweats.

- ALL can involve the central nervous system (CNS), causing headaches, seizures, and neurological deficits.

Chronic Leukaemias (CML & CLL)

- Insidious onset over years, often detected incidentally on routine blood tests.

- Fatigue, weight loss, and night sweats.

- Lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly, especially in CLL.

- CML may present with abdominal discomfort due to splenomegaly and a high white cell count.

Investigations

Acute Leukaemia

- Full blood count (FBC): High or low white cell count with circulating blasts; anaemia and thrombocytopenia are common.

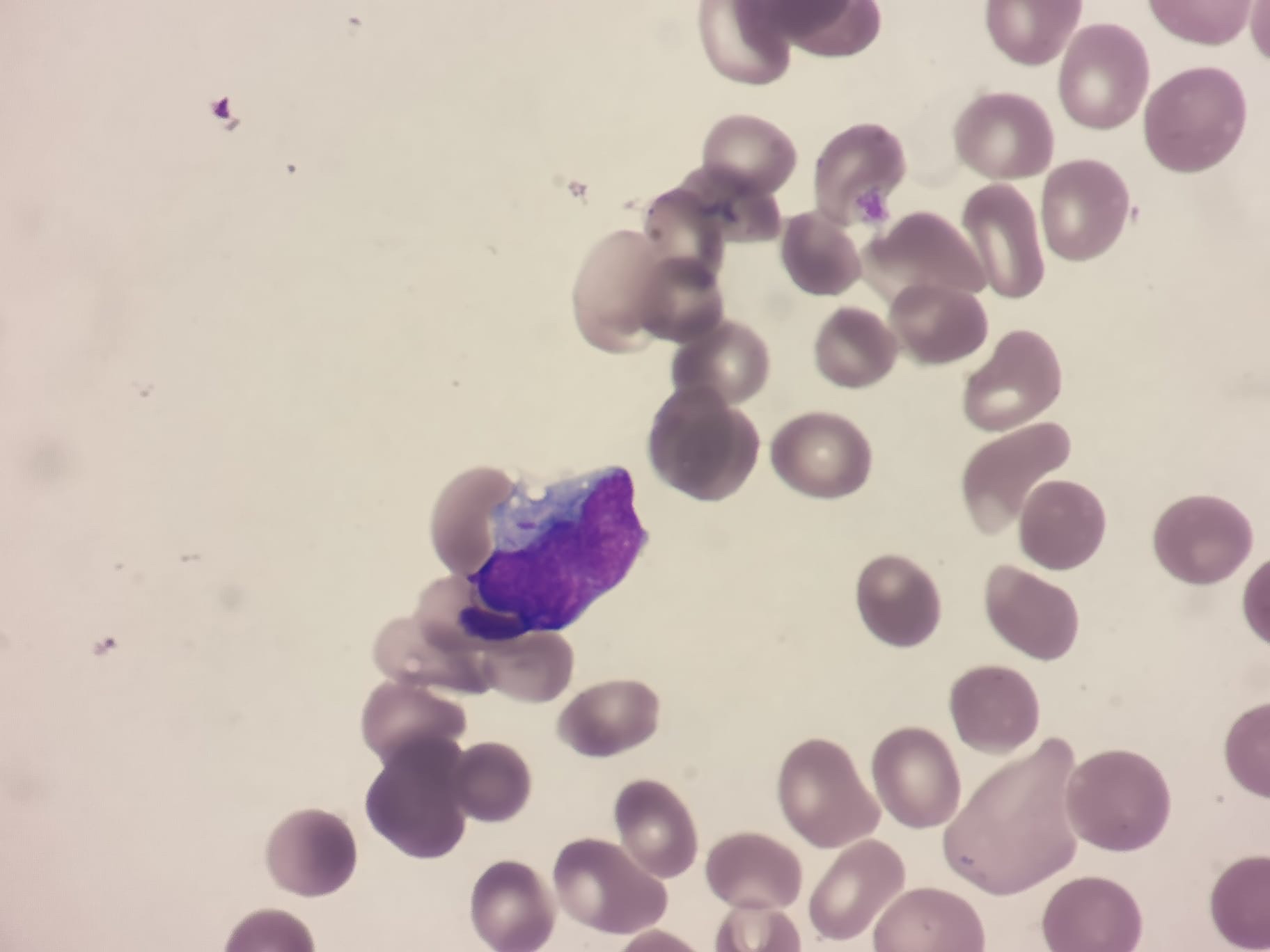

- Blood film: Presence of blasts.

- Bone marrow biopsy: Confirms diagnosis with >20% blasts.

- Cytogenetics: Identifies translocations such as PML-RARA in acute promyelocytic leukaemia (APL).

Chronic Leukaemia

- FBC: Leukocytosis in CML; lymphocytosis in CLL.

- Blood film: Smudge cells in CLL; left shift (immature myeloid cells) in CML.

- Bone marrow biopsy: Hypercellular marrow with mature cells.

- Cytogenetics: BCR-ABL fusion gene in CML.

Management

Acute Myeloid Leukaemia (AML)

- Intensive chemotherapy with daunorubicin and cytarabine.

- Bone marrow transplantation for high-risk or relapsed cases.

Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia (ALL)

- Multi-agent chemotherapy.

- CNS prophylaxis with intrathecal methotrexate.

- Bone marrow transplant for high-risk patients.

Chronic Myeloid Leukaemia (CML)

- First-line treatment with tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) such as imatinib or dasatinib.

- Long-term suppression of disease with excellent survival rates.

Chronic Lymphocytic Leukaemia (CLL)

- Early-stage disease is often observed without treatment.

- Symptomatic or high-risk disease is treated with targeted therapies like BTK inhibitors (ibrutinib) or BCL-2 inhibitors (venetoclax), often combined with monoclonal antibodies like rituximab or obinutuzumab.

Prognosis

- Acute leukaemias progress rapidly and require urgent treatment. Survival rates vary: AML has a 40-50% survival rate in younger patients but much lower in the elderly. ALL has a 70-90% survival rate in children but lower in adults.

- Chronic leukaemias progress slowly and are often manageable for years. CML has an excellent prognosis with TKIs, with >90% five-year survival. CLL is highly variable, with some patients living decades without treatment.

Key Takeaways for Junior Doctors

- Acute leukaemias present with bone marrow failure and require urgent treatment.

- Chronic leukaemias are often incidental findings and may not need immediate therapy.

- Blasts in blood and bone marrow (>20%) suggest acute leukaemia.

- CML is driven by BCR-ABL and treated with TKIs.

- CLL is often indolent but requires treatment in high-risk cases.

Leukaemia is a complex but fascinating field in haematology. Junior doctors play a vital role in recognising its presentation, initiating investigations, and understanding treatment pathways.

Want to learn more? Join our in-depth haematology course at HaematologyForDoctors.com!